- Home

- Nick Davis

Competing with Idiots

Competing with Idiots Read online

this is a borzoi book

published by alfred a. knopf

Copyright © 2021 by Nick Davis

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Davis, Nick, [date] author.

Title: Competing with idiots : Herman and Joe Mankiewicz, a dual portrait / Nick Davis.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020052645 (print) | LCCN 2020052646 (ebook) | ISBN 9781400041831 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593319703 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mankiewicz, Joseph L. | Mankiewicz, Herman J. (Herman Jacob), 1897–1953. | Motion picture producers and directors—United States—Biography. | Screenwriters—United States—Biography. | Motion pictures—United States—History—20th century.

Classification: LCC PN1998.2 .D378 2021 (print) | LCC PN1998.2 (ebook) | DDC 791.4302/33092273 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020052645

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020052646

Ebook ISBN 9780593319703

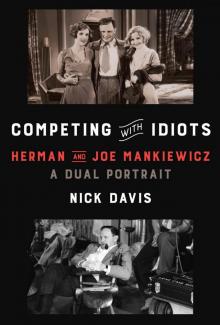

Cover images: (top) Herman Mankiewicz during production of Laughter, 1930. Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts; (bottom) Joseph L. Mankiewicz during production of Cleopatra, 1962, by Philippe Le Tellier / Paris Match / Getty Images

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

ep_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

For Jane

Contents

Prologue

Part One

Chapter One: Rosebud

Chapter Two: Gertrude Slescynski

Chapter Three: The New Yorker

Chapter Four: Yes, The New Yorker

Part Two

Chapter Five: Hollywood

Chapter Six: Trapped

Chapter Seven: Monkeybitch

Part Three

Chapter Eight: American

Flashback: Fratricide

Chapter Nine: A New Heart

Chapter Ten: Ships in the Night

Chapter Eleven: Eve

Part Four

Chapter Twelve: No Way Out

Chapter Thirteen: Hooray for the Bulldog

Chapter Fourteen: Man-About-Town

Chapter Fifteen: A River in Egypt

Chapter Sixteen: Legacy

Acknowledgments

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Photographic Credits

PROLOGUE

It’s only when you stop knowing everything that you can start to know anything at all.

It was 1988. I was twenty-three years old and walking through Central Park with my dad. We were coming from the French Consulate, it was a lovely spring day, and Great Uncle Joe had suddenly turned into a Mystery.

All my life, Joe Mankiewicz had played a distant second fiddle. In no way could his work or life measure up to that of his big brother Herman, my maternal grandfather, the beloved legendary Hollywood figure who, while drinking himself into a memorable early grave, scattering brilliant one-liners like chicken feed for everyone to peck at, had also written some of the best screenplays in Hollywood’s golden age, cowriting with Orson Welles what was quite clearly the greatest movie of all time, Citizen Kane. My grandfather’s legend was secure, at least in my mind.

The sense I’d inherited about his younger brother Joe, on the other hand, was that first of all, Joe wasn’t nearly as good a writer as Herman. To begin with, my understanding was that Joe’s 1963 epic, Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, was as big a bomb as the Hollywood system ever churned out, and that basically everything else Joe had ever done, with the grudging exception of All About Eve, was almost embarrassingly overwritten, whereas nothing in Herman’s oeuvre, including of course The Pride of the Yankees (highlighted by the immortal line “Lou! Lou! Lou! Gehrig! Gehrig! Gehrig!”) was anything other than eminently quotable. But more than that, there was the notion that Joe simply wasn’t a very good guy; it was part of the air I breathed that Joe Mankiewicz was a man who had misplaced his decency at birth and never even bothered to look for it.

But now this afternoon at the French consulate was changing everything. In the first place, that the entire nation of France had honored Joe with something called the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, struck me as totally amazing. How could a man who’d made two or three good movies (I was dimly aware that Joe should get credit for a couple other movies I’d never much bothered with, like A Letter to Three Wives and Suddenly, Last Summer) and one historically rotten epic, actually be awarded a national honor by an entire country? I knew of France’s bewildering devotion to Jerry Lewis, so I recognized the nation had a questionable barometer when it came to matters of cinematic taste—ah, youth—but were the French standards such that they would venerate the man who’d made The Barefoot Contessa, (which I’d once passed while flipping channels, cringed at the florid and ham-handed dialogue, and moved scornfully past)? As I considered the simple ribbon and medal that the French ambassador had pinned to Joe’s lapel that afternoon, the highest honor the nation bestowed and one rarely given to foreigners, I started to sense that maybe it wasn’t entirely fair to have reflexively condemned the man to the outer ring of movie directors, relishing the category in which Andrew Sarris had lumped Joe’s work: “Less than Meets the Eye.”

Joe and Claudette Colbert at the French Consulate at the ceremony where Joe was honored with the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, 1988

But in the second place, and more important, was Joe himself. This kind, unassuming, seemingly modest older man who had greeted me so warmly that afternoon, who twinkled with delight as he’d introduced me to Claudette Colbert, the man who had spoken so wittily and self-deprecatingly when the French ambassador asked him to say a few words, shaking his head and smiling down at the ornate yellow carpet when others praised his work…he looked gentle and decent, and quite a lot like my beloved Uncle Frank. Frank was Herman’s younger son, my mother’s brother and one of my favorite relatives—funny and smart and humane, and in my imagination probably the closest thing to what Herman himself must have been like. But that afternoon it was Joe, pudgy and wrinkled like a chewed-up dog toy, who seemed to emanate nothing but gentleness and humanity. He had grasped my hand warmly when we parted, and patted my hand with his sandpapery fingers, a gesture of such intimacy that it made me miss, completely and utterly, my mother, who had died when I was nine. He was my flesh and blood, this Great Uncle Joe, and he was lovely and warm and real.

So why had we never seen this man growing up? Why, when he lived less than an hour from our home in Greenwich Village, was this only the third or fourth time in my life I could remember seeing him, and the first since Mom’s funeral more than a decade before? None of it made any sense.

Dad took a deep, theatrical sigh when I asked him these questions, the kind a certain kind of man loves to take when he’s about to lay some serious shit on his son. Then he told me a story about my mom.

Dad had always been careful not to overwhelm me with stories about her. He knew I missed her, knew I’

d loved her, but I think he also felt that since she’d died when I was so young, my own memories of her were fragile treasures, things that might break or, worse, alter and be replaced, if too many other people’s memories were larded on top of my own. So Dad and I had settled into a comfortable respect for my memory of my mother, and stories about her were told sparingly. But this one, he said, could no longer be avoided, especially since I was asking about Joe. It was something, Dad told me, that he was sure Mom would have wanted me to know if she had lived….

In the fall of 1958, Johanna Mankiewicz had just graduated from Wellesley, and she had come to live in New York City. She could have decided to go back to California, where she was from, but I’m not sure it even occurred to her. She had inherited from Herman a general distaste for most things California had to offer, and besides, New York was where Joe lived.

Since Herman had died when she was fifteen, Uncle Joe had become the closest thing Mom had to a father. He’d sent her to Europe the summer after Herman’s death, and she and Joe had both relished the evenings when she was at Wellesley and would bring her friends down to the city for the weekend to meet him. They would sit at his feet and he would tell witty stories about his experiences with Hollywood starlets, making them feel at once superior to the Hollywood world and also included in its undeniable glamour.

He was nothing if not entertaining, Mom said, and in those three or four coeds who would sit at his feet, you could see he’d found a perfect audience—educated, earnest young women who knew about the things Joe cared about—Literature, Art, Theater—but weren’t so snobby, unlike other members of the New York intelligentsia, that they would reject Joe outright just because he was a successful Hollywood movie director. In fact, to them he was able to downplay his success out west and present himself as someone who’d shunned the whole damn business—Joe had moved east for good in 1951—even as he continued to direct successful movies. It’s easy to imagine Joe getting serious points and puppy dog stares from the young ladies at his feet as he modestly put off any suggestions that he was actually a quite principled fellow, tapping his pipe occasionally before sticking it back in his jaw, clenched and grinning. Young women had always been fond of Joe, not merely as a sexual creature, but as an educated, literate, psychologically astute older man who listened to them and made a much greater effort to understand them than their boyfriends, husbands, or fathers did.

And in the months after Mom had graduated from college, Joe remained the paragon. At the time, Joe and his wife Rosa were splitting their time between two homes—one a grand eleven-room apartment on Park Avenue, and the other an elegant nineteenth-century stone structure they rented in Mount Kisco. During the frequent absences of Rosa, who had long been characterized as mentally unstable and that autumn seemed to have fallen into one of her periodic ruts, Joe would often ask my mother to step in and play the role of hostess at his cocktail parties and dinners. For Mom, all of twenty-one years old and newly out in the world, it was heady stuff, having to decide whether the Moss Harts should sit next to or across from the Bennett Cerfs, and where exactly to place the Averell Harrimans. She loved it, but at the same time she recognized the basic unreality of it; during the day she was working for forty-five dollars a week at Time magazine and starting to learn a few things about the real world. But rubbing shoulders with the sort of people she did at Joe’s was always thrilling, and a party at Joe’s was never dull. After all, All About Eve’s Margo Channing’s famous pre-party warning—“Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night!”—hadn’t come from nowhere. It had come from the life of Joe Mankiewicz.

And when the party was over? Like her father, Joe wasn’t any less witty when the liquor stopped flowing and the guests grabbed their coats and left. In fact, Mom said that Joe one-on-one was as crisp as ever. His wit was in many ways as sharp as Herman’s—more moralizing, to be sure, less free-wheeling and spontaneously brilliant—but it had a consistency and a grounded quality that Herman’s lacked. There was, in both Joe’s work and his life, a solidity above all else that my mother had never experienced from her own father. The truth is, Joe was an unqualified success, unlike her dad—but more than that he was of the world, in the world, a contributor to the way things actually were, not a fantasist of the way things might have been. Unlike Herman, he dwelt in the real world, even though he may have loathed so many of its narrow-minded conventions.

So it was with no small alarm that on the autumn Saturday in question Mom received so many calls from her usually stoic uncle. Joe was staying at the Park Avenue apartment, and he couldn’t seem to rouse Rosa on the telephone up in Mount Kisco, where he’d left her the evening before. Rosa had been troubled for a long time, and Joe’s house had witnessed many uncomfortable scenes between Joe and the former Rosa Stradner, some involving knives, some involving scissors, all involving a good deal of screaming. Rosa had been in and out of sanatoriums from 1941 on, and while today we might have classified her as bipolar, and found the sensitive combination of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers to keep her steady at least, back then the sensitivity was a more general “tut, tut, poor Rosa” that surely left the poor woman feeling just as isolated.

When they finally spoke, Joe told Mom that he was worried. He’d been unable to reach Rosa and he asked, almost casually, if she’d be able to accompany him up there to see if everything was okay. Mom dropped her plans for the afternoon—later she said she couldn’t remember for sure but thought they might have involved Bonwit Teller—and met Joe at his apartment. They called Mount Kisco again and reached a caretaker who told Joe that Rosa was asleep and that everything was fine, but Joe told my mom that that didn’t sound right, so the two of them decided to travel up to Mount Kisco together.

The drive takes no more than fifty minutes, and on a brisk autumn afternoon, the leaves along the Saw Mill River Parkway were turning a nice golden yellow, with the sun dappling shadows on the cars that sped along on their weekend jaunts. But the mood in the car could hardly have been pleasant. Of course, the two Mankiewiczes in the car did not discuss what they were doing or their feelings or trepidations about what they might find in Mount Kisco. My family has long enjoyed an easy irony about itself: for people who made their living through words and communication, almost nothing of any real importance got discussed in a serious way. So while the mood may have been tense, it was undoubtedly masked by quips, witticisms, even stories from both of them—things that would bring to the Mankiewicz mouth a customary grin, a curling up of those flattish lips into a smile that can never be wholly divorced from pain. For the Mankiewiczes, it’s a wonderful, real feeling—the feeling that the listener and the speaker share the certainty that the world is an absurd place, filled with morons, and that the best we can do is point it out to each other and share laughs at the world’s unknowing expense. In fact, to a Mankiewicz, what went on in that car on the drive to Mount Kisco—heading together toward an uncertain fate, pushing away feelings of anxiety and dread with lively talk and playful digressions—was pretty much the definition of intimacy.

The house at Mount Kisco was a large stone structure with hardwood floors, a massive fireplace, and exposed oak beams. The yard was expansive, part wooded, part lawn, and surrounded by a winding stone wall straight out of Robert Frost. On pulling the car into the driveway and walking toward the front door, Joe told my mother to check upstairs while he looked downstairs. The bedroom, of course, was upstairs.

Years later Mom still described it as the great horror of her life, walking into that bedroom and seeing what she saw: the corpse of her aunt, askew on the mattress, the room in disarray, a stench already wafting. The feeling of having been used in the incident, though, took a few years to hit Mom fully—Dad reminded me that when he and Mom got married the next year, it was Joe who walked Mom down the aisle—but when it did, she found it hard to forgive Joe for those simple words: Josie, go upstairs. It wasn’t just that she felt

the whole thing had been a setup—she suspected that Joe had known Rosa was dead the entire day—but that Joe had chosen her to be the instrument by which a suicide would be discovered.

Why had Joe felt the need to orchestrate the scene that way? If he really suspected his wife was dead, why couldn’t he have asked someone to go check on her? Or, better yet, check on her himself? Isn’t that what husbands do for wives they worry about? What kind of man does that to his niece?

Dad wasn’t able to tell me too much more that afternoon, but I knew that the answers to these questions could probably be found in the relationship between Joe and Herman. They were two of the most accomplished brothers Hollywood had ever seen—even now, more than sixty years after their greatest successes, most people still know about Joe’s All About Eve and Herman’s Citizen Kane (the battle over screenplay credit would rage far beyond Herman’s lifetime, and neither Pauline Kael’s famous essay “Raising Kane” nor David Fincher’s movie Mank will ever put an end to the debate over what Herman contributed and what Orson Welles did)—but at bottom, they were brothers, born nearly twelve years apart, bound together in a relationship of such complexity—full of passion and pride, hatred and love, jealousy and rage—that even five years after Herman’s death, it’s possible Joe simply couldn’t resist the urge to direct a scene where the focus of all the horror and pain he could muster would be his late brother’s daughter.

But what drives a man to such extremes? What did Herman do to Joe to engender such unconscious hostility? Was Herman such a powerful figure for Joe that years after his death, he was still calculating his every move through a prism of how it might play to the Herman in the back row of his imagination?

Competing with Idiots

Competing with Idiots