- Home

- Nick Davis

Competing with Idiots Page 2

Competing with Idiots Read online

Page 2

Or was Joe merely in need of human connection? Was his sending Mom upstairs merely a quick suggestion, almost a meaningless reflex?

Years before Mom’s horrifying discovery in Mount Kisco, her father had laid down the rules for film construction for his friend Ben Hecht. They included the basic moral strictures of good guys winning, bad guys losing, and both the hero and heroine remaining virgins, which stood in direct contrast with the villain, who, at least until the final reel, “can have as much fun as he wants—cheating and stealing, getting rich and whipping the servants.”

But in his litany of storytelling chestnuts, Herman neglected one of the most familiar: an opening scene that leaves us with nothing but question marks, followed by a flashback dissolve…

PART ONE

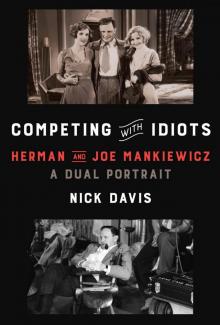

Will you accept three hundred per week to work for paramount pictures? All expenses paid. The three hundred is peanuts. Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots. Don’t let this get around.

—Telegram, Herman J. Mankiewicz to Ben Hecht, 1926

CHAPTER ONE

ROSEBUD

Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn’t get or something he lost. Anyway, it wouldn’t have explained anything. I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life. No, I guess Rosebud is just a piece in a jigsaw puzzle, a missing piece.

—Citizen Kane

As a young boy, Herman Mankiewicz found himself in trouble nearly every day, and for one infraction or another, he often found himself virtually imprisoned in his room to think about what he had done. It was practically an afternoon ritual. But as he later told a psychoanalyst in Hollywood, what remained most vivid about those enforced solitary confinements was not the thought he gave to his alleged misdeeds or any shame over having committed these dastardly acts, or even the deep and profound rage at his father (or, less frequently, mother) for the enforced exile, though the anger was severe indeed and would remain with him forever, but the exquisite feelings he felt in being alone, the sights he saw and the smells and sounds that surrounded him outside his window in New York City. Most of all what he remembered was a powerful, almost primal urge to share those feelings with the whole world. He thought that if he were somehow able to convert his actual, entire experience—the orange tint of the afternoon sun on the bricks on the building opposite his window, the sound of a breeze, the snapping sound of the lines of laundry in the tenement courtyard—into something the whole world could also feel, life would be worth living. Anything else would be a misery. To share this life, he thought, to get the world to see through his eyes—that was all he wanted in the world, but to his young mind it was also quite obviously an impossibility. How could one will the entire world to see what he saw? The situation made him deeply depressed.

Herman in NYC, c. 1903

So while Herman Mankiewicz later said that there was no better time to be born in New York City than 1897, he was equally convinced in the first few years of his life that he would rather have been anywhere else in the world. As well as a deep and urgent need to get the world to share his vision, the feeling of being in not quite the right spot was one that he would grow painfully familiar with throughout his life. But what Herman didn’t know, at least not in so many words, was that the trait was an inherited one, passed from generation to generation like blue eyes in a Norwegian family or red hair in a Scottish one, the not-quite-belonging trait, Mankiewiczian to the core. It was what Herman woke to every morning of his young life in New York City.

New York at the turn of the twentieth century was not so different from New York today, or at any point between then and now: the center of the world for those living there, a colorful, swirling, mad, loud, impossible, smelly place riven by wild class divisions and unacceptable cruelty jutting up against magnificent examples of the most graceful humanity imaginable; and for those elsewhere, a spot to be avoided, or at best tolerated if one had to pass through. The almost permanently discomfited expression on the face of Herman’s dad, Professor Franz Mankiewicz, always suggested to Herman that he too wished to be elsewhere. He wished to be elsewhere than in New York in the first few years of Herman’s life, wished to be other than a schoolteacher, wished to be married to a woman other than Herman’s mother, wished to be born in a different century, a different country, into different skin.

Franz’s discomfort had as much to do with the world as it did with himself. Like many dogmatic personalities, he was often bewildered by the realm outside his head. Raised in Frankfurt by a domineering father himself, Franz had inhaled a Teutonic sense of self-discipline and order, and the world’s inability to follow along never ceased to amaze and infuriate him. As a schoolteacher, he was beloved by the students, who cared as passionately as he did about his subjects. Those who didn’t he heaped with contempt, as well as a profound and deep inability to understand their lassitude or lack of interest. This discomfort—what Herman and Joe used to love to make fun of when they were out in Hollywood in the 1930s and Franz would come for one of his infrequent visits—was plainly etched on Franz’s face, and while hundreds of students passed through Franz Mankiewicz’s classrooms over the years, he had only one first son. One first son on whom he could pin all his hopes and dreams—one son to disappoint and enrage him.

Franz Mankiewicz

Young Herman learned early on that he had become a magnet for his father’s displeasure. It wasn’t just that Herman was a continual disappointment to his father—he was, of course; Herman all his life would tell of bringing home a 97 on an exam only to be barked at: “Where are the other three points?” (It was the “where” that got Herman going. “Where? They fell out of my pants, I dropped them in the gutter, I stuffed them up my nose…”) If Herman responded by saying that nobody else in class got more than a 90, Pop would say, “The boy who got 90, maybe it was harder for him to do that than for you to get 97. It’s not good unless it’s your best.” To Franz, Herman later said, bragging about being smart was no different than bragging about “having blue eyes. It’s just a characteristic. It’s what you do with it that matters.” On those rare occasions when Herman did meet the high standards his father had set for him, Franz never praised him. It’s hard to imagine it even crossed his mind to do so.

Looking at pictures of the man when I was growing up, or, more menacingly, the portrait of the stern face that stared down from its pride of place hanging above my grandmother’s mantel in Brentwood, it was almost impossible to imagine that Franz Mankiewicz was ever young. In picture after picture, the frown, the worry, the concern of age weigh heavily on every single feature. He was married at the age of twenty-four, but could he ever have walked with a bounce in his step, or sung in the bathtub, or had a moment of genuine passion with his wife, or anyone else for that matter, that didn’t involve yelling? As a young immigrant in New York, the highly educated Franz had become a reporter for one of the three hundred German language papers in the city. He was effective, smart, and hardworking, with a fierceness for life that inspired in those around him a genuine feeling of respect. For his firstborn, though, that feeling was closer to fear. “Pop was a tremendously industrious, brilliant, vital man,” Herman said later. “A father like that could make you very ambitious or very despairing. You could end up by saying, ‘Stick it, I’ll never live up to that and I’m not going to try.’ That’s what eventually happened to me.”

The portrait of Franz, seen here on Joe’s mantel in Bedford, New York, in the 1980s

To Herman, Franz was the hot and unrelenting sun around which he rotated and which threw all of Herman’s most unpleasant features into relief, for Franz and everyone else to see; thus exposed, Herman would be met with the fiercest disapproval, judgment, and discipline. Above all, discipline. Like most German immigrant fathers, Franz didn’t spare the cane, and his regular beatings of Herman became part of family lore. It got so when Herman saw his father with a look in his eyes, he would merely go to Fra

nz and bend over, even when he had no idea what particular sin he’d committed. While Herman later spun it into an amusing anecdote, and more than that, wove it into the fabric of his existence, behind the funny story was an undeniable truth: Herman Mankiewicz had come to loathe his father. Indeed, though he knew it wasn’t true, he later felt that he had almost no memory of feeling anything but hatred for the man. So dominant was the feeling, and so thorough was his assumption that children hated their parents, it became the source of one of the Hermanic witticisms that was passed down in the family as if it were Talmudic logic.

The example given was always spinach, that most detested of vegetables. “I hate spinach,” the young child would say, only to be told by Herman, “No, you don’t hate spinach. You despise spinach. You hate your parents.”

That story was told frequently when I was growing up, just about whenever my older brother Timmy or I said we hated something, like spinach or sweet and sour pork. My problem, early on, was I didn’t get the joke. It took me years to understand that it was based on the strange truth that Herman assumed, profoundly and deeply, that you did hate your parents, that everyone did, and as a result that trait got baked into the family DNA, as much as the humor. In fact, only if you admitted you hated your parents would you fall into line, in line with all the Mankiewiczes of course, but most of all in line with Herman. And nothing was better than to be like Herman.

For from the beginning of my own life, I knew one thing: Herman J. Mankiewicz, Mom’s dead father, the “Gopa” we never knew (to the “Goma” we did, the “poor Sara” of so many long-suffering years in Hollywood), was the funniest man who ever lived. Uncle Frank told funny stories, Uncle Don was funny responding to others, but their father—Herman—he was nonpareil.

Two quick examples, the kind you find in books about Hollywood’s earliest batch of screenwriters from back East and their notorious self-loathing. First: a studio head fires Herman, tells him that not only will Herman never work at the studio again but the man assures him he’ll make sure Herman never works at any studio in town. Herman looks at the man and says, “Promises, promises.”

Second: watching Orson Welles walk by on the studio lot: “There but for the grace of God, goes God.”

Of course Herman was far from the first to transform pain into comedy, but what seems to have given Herman his greatest satisfaction growing up was his stealth comedy, a sense that he could mock someone—usually his father—without the target’s even realizing it. To the end of his life, Franz would be the butt of both of his sons’ humor, and what they loved most was how little he seemed to understand why what he did was funny to them.

In the early 1930s, Herman and Joe were in Hollywood working on a script together—some biographers might say declaratively that it was Million Dollar Legs, the W. C. Fields movie on which Joe received a writing credit, and for which Herman was one of the producers, but there’s no knowing what movie it was—and they came across the French word for town, ville, which Herman took delight in pronouncing “veal,” an obviously Americanized pronunciation. Joe would quietly correct his big brother, leaving off the l’s and making it sound overly Gallic: “Vee-yah.” The brothers go back and forth on it for a while, Joe insisting that by French rules of pronunciation it should be “veeya,” Herman insisting right back it’s an exception to the rule. Then they realize that the man who would know the answer happens to be in New York City, a brilliant professor and linguist just a long-distance phone call away. So they call Franz, he picks up the phone and says hello, they say “It’s Herman and Joe, Pop. We’re having an argument over the correct pronunciation of the French word v-i-l-l-e, is it ‘veeya’ or ‘veal’?” Franz says “veal” and hangs up the phone.

Herman and Joe both loved telling that story. The man hadn’t heard from his sons in weeks, maybe even months. But niceties, warmth, kindness—all of that seemed beyond Franz Mankiewicz. He had answered their question. The purpose of the call had been accomplished. It cost a lot of money to talk long-distance. And so he’d hung up.

But there is a crucial difference between the ville story and how Herman experienced Franz in his childhood: the difference was Joe. Joe gave Herman an ally in the lifelong battle for respect from his father, and also another soldier in the silent war against him, a war whose explosions had been fights and one-sided gusts of laughter from Herman until Joe’s arrival on the scene. But for Herman, the age difference of nearly twelve years meant that Joe would not be a full ally until adulthood—in childhood, it was Herman against Franz, and it was a bruising battle.

And what of Herman’s mother? How can it be that the family lore is so focused on Franz, and that Mama gets such scant attention? As an adult, Herman virtually dismissed his mother, telling one friend that his mother had been a typical German hausfrau, “a round little woman who was uneducated in four languages. She spoke mangled German, mangled Russian, mangled Yiddish and mangled English.” Goma later told Herman’s biographer Richard Meryman, “For his mother, he had a kind of, not contempt, it’s too strong a word, but certainly no great regard.” Herman thought of her, or so he said, as little more than someone to darn the socks, cook the meals, and make sure that everything was in its place. He grew, in fact, to be as indifferent to her as his father was—one famous family anecdote tells of the absentminded professor proudly telling his wife that she should be proud of him, for that day, on the street, he had seen two women coming toward him. “I concentrated very hard,” Franz said, “and I remembered the name and said, ‘How do you do, Mrs. Neuschatz?’ ” And who was the other one, she asked him. He didn’t know. “That was me,” said his wife.

But a son who wavers between contemptuousness and indifference to his mother had most likely once felt quite differently toward her…

The morning had been a pleasant one, and Herman told his wife about it years later with great feeling. Mama had taken him to the butcher’s first, where Herman always loved walking on the sawdust-covered floors, imagining he was in some kind of jungle, with the sausages hanging down from the trees and the enormous slabs of animal laid out on the butcher’s blocks, white-apron-clad warriors slicing and hacking, cutting away at the beasts, who Herman knew had been quite recently terrorizing the villagers, circling their huts and eating their young. After the butcher’s had come a rarer treat still, a visit to Mama’s friend, the lady with the flower dress who Mama had tea with. The woman had given Herman a red sourball as a treat, which he’d plugged away in his right cheek until it had caused a small sore there and he’d shifted it to the other cheek. The day had been easy, fun, not even noticeable as a day, and only later, in thinking back, did Herman realize that he must have been dribbling juice from his sourball on his shirt all afternoon. But then, when they came home, there was Papa, inexplicable—why? Why in the middle of the day?—and he’d become incensed at the sight of the stain on Herman’s shirt, and directed all his fury toward Herman. When the whip came out, the images were frantic and cruel—Franz unstrapping the belt from over the door handle where he always kept it, and wiping his hands on the belt, as if he were a surgeon and it were a rag and he was drying his hands before an operation—and the whole time, Herman was never particularly worried. He’d been beaten before, of course, and grown so accustomed to the spankings and beatings that he no longer really dreaded them, or even their outcome, which was a bottom that would be sore if not outright numb and paralyzed for a few hours—but this one was different. Because Mama was there. She was there, and she was raising her voice—surely she was raising her voice, she must be—to defend Herman, to tell Franz that it was her fault, not to punish the boy, he’s five, and he’d been given the sweet by my friend, Franz, don’t take it out on him. If I hadn’t taken him with me, this wouldn’t have happened. I will wash the shirt, the shirt will be as good as new, you need not worry.

But the words never came. There was no defense. Mama left the room without a word, and when Herman went

in to the bedroom later that afternoon to take his nap, the rage flowed like tears, bitter and furious. He would fight his father because he had to, because no one else would. But Mama, he decided, he would no longer think about. She was to be obeyed, fine, but never again respected, never again a source of love. He wouldn’t let it happen. The full-throated love and trust was gone forever.

* * *

—

One of the great debates in film history, to say nothing of the insane battles waged over the same issue in my family, is who wrote what in Citizen Kane. Much of that, of course, had to do with the enormity of Orson Welles’s ego, and his insistence, which to be fair was also a shrewd business move, on being known as a one-man band, an auteur before we even knew the meaning of the word. As a result, to Goma’s eternal regret, Herman’s original contract sold his right to any claim of authorship of Kane. While the debate has raged for nearly eighty years with no obvious resolution (despite what Goma felt), two elements of the script’s provenance have never been in dispute. The first is its startling structure, with the reporter’s quest for getting to the truth about Charles Foster Kane leading to a series of overlapping sequences and chronological restarts that still feels strikingly modern. The second is Rosebud, one of the most famous words in movie history, the word that Kane utters on his deathbed that sets the biographer’s search in motion.

Both inventions were Herman’s. Even Welles himself admitted: “Rosebud was pure Mank.”

Of course, Welles also derided Rosebud as “dollar book Freud.” The idea that on his deathbed a great tycoon would dredge up a long-dormant memory of a childhood toy, now all but forgotten, as a symbol for his lost innocence does sometimes seem a simplistic gimmick to stand at the center of filmdom’s greatest masterpiece.* But it’s also powerful, in part because, as Pauline Kael and others have pointed out, Citizen Kane isn’t Shakespearean tragedy, but really, at its heart, a great movie movie—the greatest movie of all time, maybe, but it earned its A-plus as a B movie, as much an emblem of pop culture as transcendent work of art. And therefore, it isn’t in spite of the Rosebud gimmick that the movie works so well, as Welles may have hoped in his moments of greatest artistic ambition, but rather because of it—because the entire movie’s narrative is driven by the meaningless conceit. “Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn’t get or something he lost,” the reporter Thompson speculates at the end. “Anyway, it wouldn’t have explained anything. I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life. No, I guess Rosebud is just a piece in a jigsaw puzzle, a missing piece.”

Competing with Idiots

Competing with Idiots